The second president of the United States, John Adams, knew that education would be the firmest foundation for American society. He sagely counseled, “I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy,…in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.”

Americans have long cherished the belief that it is the duty of each generation to afford its heirs the opportunity to provide themselves a better life. Through education and self-actualization, our children might one day eliminate pestilence and poverty giving rise to an era of global peace and prosperity as yet unimagined. Who among us would dare wish for the contrary?

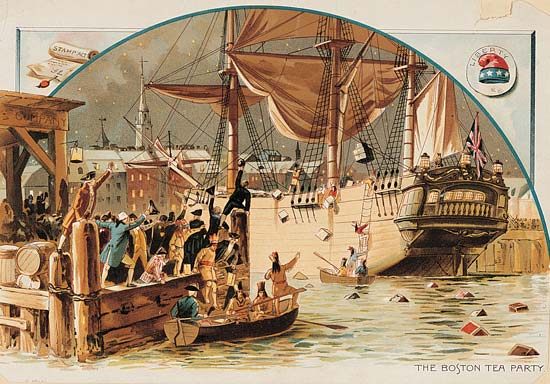

Two centuries ago few children achieved little more than the rudiments of reading and writing. A century later most children attained modest levels of functional literacy. A few decades ago child labor laws removed children from the hazards of exploitative and dangerous labor practices saving countless thousands of limbs and lives. Today, most children acquire a high school diploma.

We have come so far, but we have so far yet to go!

Today, much of what students are expected to learn in high school has been discovered in the years since their grandparents graduated. The children of current students will be obliged to acquire knowledge that has yet to be discovered. What Sir Francis Bacon referred to as “The Knowledge of the State” is doubling every seven years, but funding for the public schools, as a percentage of the Gross National Product, has not changed appreciably in decades.

This generation risks becoming the first American generation to fail to meet the challenge of readying students for the workplace that awaits them. And why is this? Taxpayers do not see the need for improving working conditions for teachers or learning conditions for children.

Nowhere is this more evident than with the issue of class size.

For years now, educators have been informing anyone who will listen that large class size negatively impacts student achievement. Well-designed, longitudinal research was performed in Tennessee. The research clearly demonstrated the positive effects of reduced class size in the early elementary years on student achievement in subsequent years. The conclusions were unequivocal.

Yet, there are still ideologues who claim that lowering class size constitutes “throwing money at the problem” of lackluster performance in our schools. They inform us that students in other countries achieve academically despite large classes while conveniently omitting the fact that most of those countries “weed out” low achievers by the age of fourteen by placing them in apprenticeships or in the workforce.

The student load confronted by teachers in any high-poverty school system is simply overwhelming, and the welfare of children is not served by increasing compensation for educators if that means returning to a more overcrowded classroom each autumn. Why should the concept of workload stress be any less relevant for educators than it is any other human undertaking?

Let’s assume there are two footraces this weekend. The first is fifteen kilometers and the second will cover thirty. Which race do you suppose will have the highest percentage of drop-outs? Which race will be run at the fastest pace?

Let’s put two barbells on the floor. The first weighs 150 pounds and the second is loaded with 300. Which barbell are lifters most likely to raise from the floor? With which weight will the lifters perform the highest number of repetitions?

Yet, we routinely place 30 students in a room with one adult (and sometimes even 40!) for nearly 300 minutes a day, despite knowing that efficiency would be improved by reducing both numbers. Now, in the Age of Accountability, bureaucrats hope to pass judgement on teachers when “educational outcomes” are less than optimal.

Even car manufacturers in Detroit learned that listening to their labor partners and slowing the assembly line produced better cars, reduced product recalls and increased morale. It is a lesson that must soon be applied to Public Education.

Think carefully, now!

All other things being equal, would you rather have your surgery done by an overworked doctor performing thirty procedures a day, or one performing half that number? When are medical mistakes more likely to occur?

Would you rather have your case tried by a public defender assigned thirty difficult and complicated cases, or one assigned only fifteen? Which lawyer is more likely to overlook something crucial to your defense?

So, should your child be sitting in a marginally equipped room with 29 classmates (or more!) and one overworked, under-compensated professional educator who corrected papers and wrote lesson plans into the wee morning hours? Can we not agree that a teacher and a child would have a better opportunity to connect emotionally and intellectually in a less cramped environment?

Elizabeth Cady Stanton once said, “To throw obstacles in the way of a complete education is like putting out the eyes.” Placing our children and their teachers in overcrowded conditions is an inexcusable hindrance to the future success of both… Therefore, the community must resolve to remove this impediment from the path to sustained academic excellence. Moreover, if we do not accept the responsibility of providing adequate resources to all learners, then many children will forever wander anonymously in the crowd of students competing for the teacher’s attention.

All children deserve a better fate.

[This commentary originally appeared in the now defunct Prince George’s Journal circa 2000.]