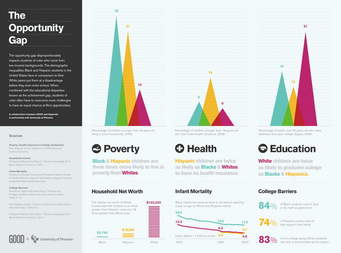

In his book Savage Inequalities Jonathan Kozol pointed out that a Maryland task force on school funding suggested to the governor in 1983 that “100 percent equality was too expensive” a proposition, and that, therefore “the poorest districts should be granted no less than three quarters of the funds at the disposal of the average district.” Decades after the Supreme Court had ruled that “separate” is inherently “unequal” and moved forward -however slowly – with desegregation, Maryland enacted a policy that suggested “unequal” education was just fine for the socio-economically disadvantaged.

More than three decades later, and a decade following the passage of the landmark Bridge to Excellence Act, based on the renowned work of the Thornton Commission chaired by Dr. Alvin Thornton, the children of Prince George’s are still experiencing the legacy of that Orwellian public policy. Just last year Worcester County budgeted approximately $17,093 per student while Prince George’s County has budgeted about $14,813. Thornton funding has closed the gap somewhat, but equity has yet to be achieved for children living below the poverty line. [See link: 2015 Per pupil Spending in Maryland ]

Nationally this year 91% of school funding, approximately $550 billion dollars, will be allocated locally for schools, mostly derived from real estate taxes. The current funding stream virtually guarantees that the quality of education will be determined by the average net worth of homes in a zip code.

Should Prince Georgian’s be heartened by the fact that our per-pupil spending has closed the gap to 86 percent of our more wealthy neighbors? Or do we owe it to our children to improve still further and, in so doing, offer ALL the children of this community the surest path to breaking the chain of poverty? Or will we allow those who have maximized their opportunities to pull the ladder up behind them? The answer to each question should be abundantly clear.

Today, two words should strike terror into the heart of every Prince Georgian with a child in school. Two words should inspire every supporter of public education in Prince George’s County to political action. These same two words need to be excised from our political lexicon and our regional rites of spring. What are these two words?

-Budget Reconciliation.

Our superintendent will likely soon be compelled to do what all effective educators always attempt when the allocations do not match the budget request: make do. As much needed line-items are deleted by the doctrine of cost-avoidance made famous by a previous superintendent, the Superintendent/CEO must deploy inadequate resources for maximum effect. What an onerous, unenviable task to befall someone who has devoted a lifetime to children.

Whose dreams does one elect to quash? Whose aspirations get trampled?

- Is it the students on the cusp of possible success who watch beneficial programs of study disappear?

- Is it the teachers who dream of reaching each-and-every student that will find themselves hopelessly overwhelmed by unreasonable class sizes?

- Is it the administrators who will witness the dismantling of effective learning environments as necessary resources are withheld?

None of these alternatives should be acceptable outcomes for our children, or the children of our neighbors.

Still, these are among the options that we face if this community does not unite behind the Board of Education and Superintendent in the struggle to furnish adequate resources to the children of our neighbors. Everyone who cares about education in this county needs to engage in the political fray that threatens the well-being of children.

We must not misdirect our efforts!

Our struggle lies with the funding authority of the Prince George’s County Public Schools and an electorate that has permitted inequities to flourish for as long as any of us can remember. Struggle we must, however, lest we be counted among those that Frederick Douglass chastised for expecting food without plowing the ground. Otherwise, what fate awaits us with the next, inevitable economic downturn?

Unlike in previous budget cycles, the County Executive, Rushern Baker, and members of the County Council are spreading the word that commitment to public education signals to businesses contemplating a relocation that Prince George’s County is a healthy and vibrant community. If we want the stability of families choosing to make a life in Prince George’s County, potential newcomers need to see a community commitment to the public schools. It is incumbent on Main Street to make doing otherwise a politically untenable position.

In the long term our elected leadership needs to establish policies and procedures that will effect full-funding for the public schools at levels that will meet the educational needs of all children at optimal levels. Our leadership must continue to demonstrate to the naysayers who resist such ideas why these policies are in the best interest of the common welfare.

Long ago this great nation recognized the error of its ways and abolished the practice of fractional apportionment of votes based on race. Perhaps, the historical moment has arrived for this community to lead the way in abolishing the practice of fractional apportionment of educational opportunities based on socio-economic status. Until such time as this goal is attained, until such time as we furnish every child a truly equal setting at the American banquet, until the entire community embraces the sacred trust of educating the next generation, in the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., “We must not be satisfied.”

[A much updated & revised more current version of a “Viewpoint” that first appeared in the now defunct Prince George’s Journal on June 4, 2001.]